Daniel Day-Lewis Can’t Save This Movie

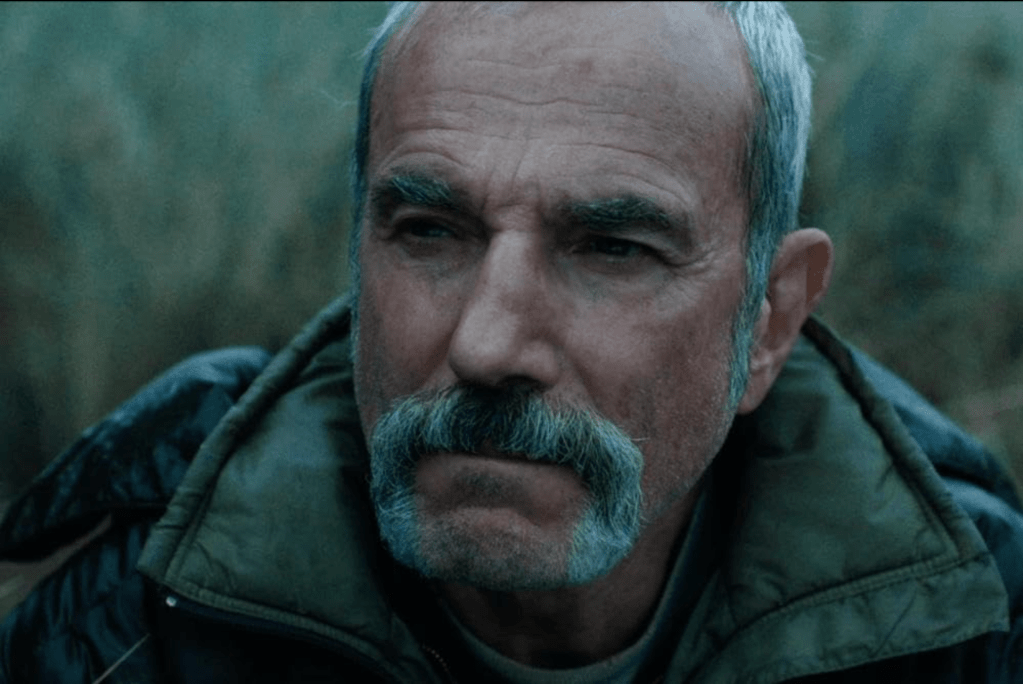

I walked out of Anemone feeling like I had watched a promising film that never quite learned to tell the story it wanted to tell. The picture puts acting heavyweights—Daniel Day-Lewis, Samantha Morton, and Sean Bean—at the center and then asks their faces and gestures to do most of the telling. That choice creates striking moments, but it also leaves large stretches of the film hollow.

Ronan Day-Lewis, directing his father, leans hard into atmosphere and symbolism instead of clear narrative mechanics. The film opens with sparse dialogue and long, deliberate scenes meant to build mood, but the accumulation of symbols rarely clarifies motivation or stakes. When repetition replaces revelation, suspense deflates rather than intensifies.

The movie depends on a handful of memorable set pieces that never quite connect. One sequence shows Daniel Day-Lewis’ character, Ray Stoker, encountering a white, polar-bear-like spirit with a human face—an image that lingers but doesn’t communicate its purpose. Another moment features a semi-transparent creature whose internal organs are visible, a striking visual that serves more as texture than explanation.

There’s also a scene with a dead, oarfish-like animal about six feet long that drifts by, its iridescent body marred by missing sections of skin. In folklore the oarfish can be an omen of seismic doom, but Anemone never follows through on that implication. Instead the image exists as an isolated puzzle piece with no surrounding picture to solve it.

The film attempts a psychological and mythic overlay, yet it rarely makes those layers speak to one another. Good symbolism should deepen character and plot simultaneously, as mirrors do in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan or the rabbits in Jordan Peele’s Us. Here the symbols mostly announce themselves and then drift offstage.

There are flashes where the approach works. A letter from Ray’s ex-wife, Nessa, sits unread on a windowsill and later a doll resembling her floats above a bed, creating a genuinely eerie, haunted moment. That scene captures the emotional residue of the past in a concrete way, proving the film can land when form and feeling align. Unfortunately, those successes are intermittent rather than cumulative.

Even the titular reference arrives like an afterthought. Ray tending to anemone flowers leads to one line of dialogue: “Are those the same flowers our father used to grow?” That single exchange nods toward a larger family myth or grief, but the movie does not pursue the famous anemone myth tied to Aphrodite and Adonis or use it to illuminate character. The result is a title that signals meaning the film mostly leaves unexplored.

Daniel Day-Lewis carries the movie with a performance that feels theatrical in the best sense—layered, patient, and often riveting. The score and sound design frequently shoulder the film’s emotional momentum, stepping in where plot and dialogue leave gaps. Still, even powerful acting and evocative music can’t fully cover for a script that withholds too much of its own logic.

Ronan Day-Lewis understands cinematic components: strong cast, vivid imagery, and an appetite for psychological exploration. What he struggles with is integration—how to let a symbol earn its narrative weight and how to convert atmosphere into meaning. The film has artistry on display but not the connective tissue the viewer needs.

Anemone is uneven and often admirable in the same breath: a collection of compelling gestures that rarely coalesce into a convincing whole. It asks the audience to roam through its images and emotions without a reliable map, which will reward some viewers and frustrate others. The movie is an experience rather than an argument, and that decision is its chief strength and its biggest flaw.