Homer’s Watercolors: A Century of Quiet Mastery

The museum displays all of its nearly 50 Homer watercolors, saluting Homer, Boston’s native son, and more than a century of collecting. Seeing the whole group in one place changes how you read each sheet, from technique to temperament. These works hold a special place in American watercolor history.

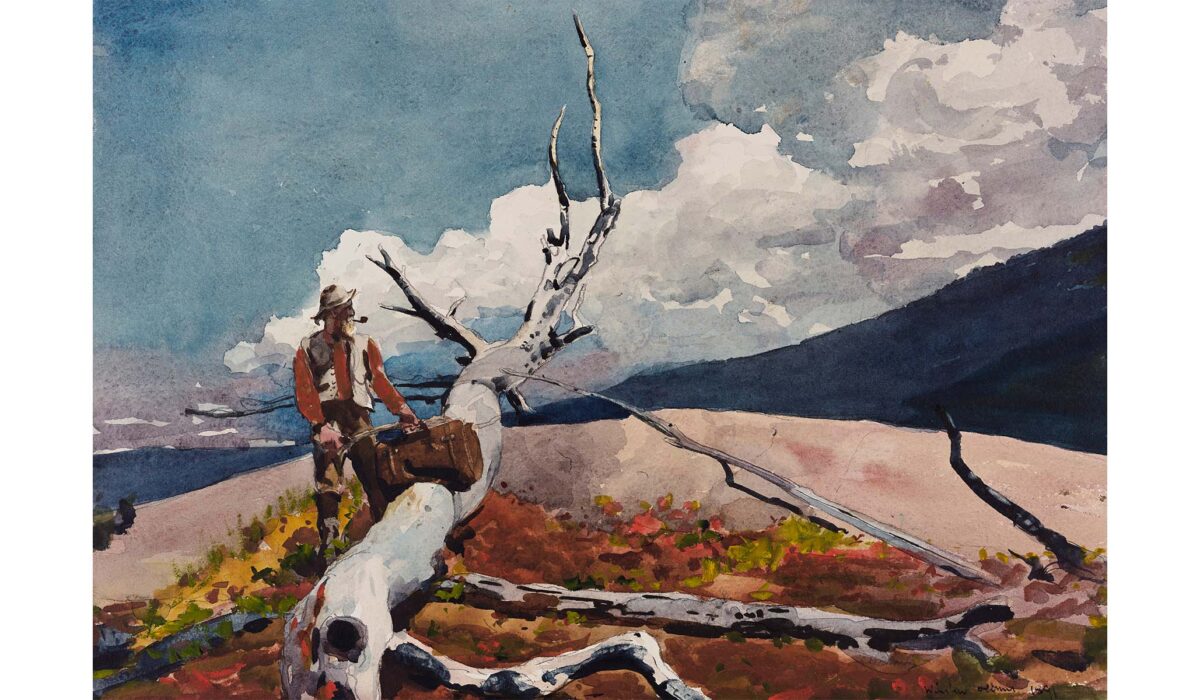

Winslow Homer’s watercolors compress big ideas into modest paper sizes. He used simple tools to get weather, light, and motion into a single frame. That economy of means is what makes these almost fifty works feel both intimate and grand.

Visitors notice repeated motifs: shoreline, figures at work, weather turning. Homer loved the coast and the ways people adapt to it, and those themes come through in study after study. Looking across the collection you get a sense of recurring questions rather than repeated answers.

Color choices surprise and instruct; Homer could be both spare and luscious. He often left paper visible, letting the white do heavy lifting for highlights and atmosphere. Those deliberate omissions are as revealing as his brushstrokes.

Light and season matter in every sheet here, from bright noon to foggy gray. Homer used watercolor to capture fleeting effects that would be difficult in oil. That immediacy is one reason the museum’s decision to assemble the complete group matters so much.

Curators arranged the display to show relationships between works across years. Juxtaposition lets you trace experiments in composition and mood. It’s a small archive that functions like a long conversation.

The conservation story behind the pieces is part of the appeal; watercolors are fragile and need careful handling. The museum’s long stewardship—over a hundred years of collecting and care—shows in how well these sheets present today. That continuity gives the works context and keeps them available for fresh study.

For scholars, the full run opens questions about Homer’s working process and sources. Sketches near finished pieces reveal shifts in line and tone. The museum’s holdings become a primary reference for anyone studying his methods.

Display design keeps the viewing intimate, encouraging slow looking rather than quick scans. Labels focus on technique and provenance without over-explaining the obvious. The result lets viewers build their own connections between image and idea.

Educational programs tied to the exhibition aim to unpack watercolor practice for newcomers. Demonstrations and talks translate visual shorthand into hands-on learning. Those initiatives help make the collection more approachable without diluting its complexity.

Public response often centers on how private these works feel despite the crowd. People comment on a single figure, a fleeting cloud, or a sharp crag as if they’ve found a small secret. That private reaction is part of Homer’s enduring power.

The museum’s nearly 50 watercolors offer a concentrated look at an American master who kept returning to similar subjects to ask new questions. Collecting over more than a century has allowed the institution to present a coherent story about practice, place, and persistence. This presentation makes Homer’s subtle provocations visible in a way single loans never could.