Rembrandt’s Workshop and the Rare Vermeer That Joins It

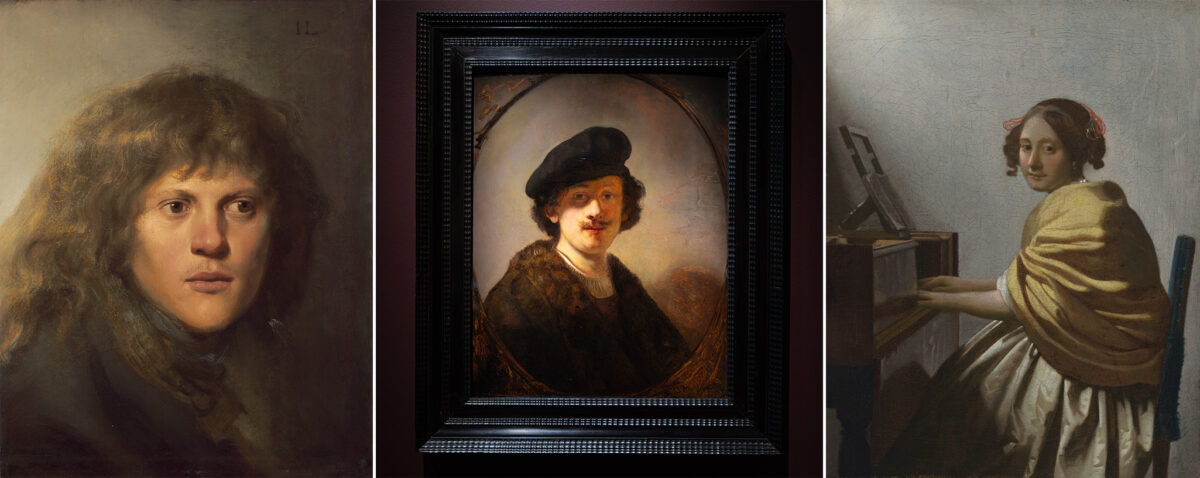

There’s a show that brings together a bustling artist’s workshop and a unique treasure from another master. It places Rembrandt’s influence front and center and sets his students’ works beside a rare Vermeer held in private hands. The contrast is immediate and instructive.

He nurtured plenty of talented students whose work is on view along with the only Vermeer in private hands. That idea — master and pupils presented in the same space as a singular Vermeer — sharpens how we read technique, ambition, and taste across generations. It’s a curatorial choice that emphasizes conversation over hierarchy.

Rembrandt’s classroom was more of a studio laboratory than a strict academy. Students learned by copying, collaborating, and absorbing the master’s approach to light, texture, and human presence. Those habits show in paintings that range from faithful echoes to bold personal spins.

Seeing pupil works side by side with Rembrandt pieces exposes subtle differences in brushwork. Some students chase Rembrandt’s rough, tactile strokes; others prefer cleaner passages and clearer outlines. Together the pieces map a spectrum of influence, not a single monolithic style.

The privately held Vermeer in the exhibition acts like a quiet antagonist. Where Rembrandt’s circle often revels in theatrical chiaroscuro, Vermeer is famously restrained, tidy, and obsessed with interior light. Placing that one Vermeer among Rembrandt’s disciples tests viewers’ assumptions about Dutch art’s variety and cohesion.

Curators have arranged these works so comparisons happen naturally, not artificially. You can move from an intimate Rembrandt portrait to a student’s answer and then to Vermeer without a forced narrative. That flexibility lets each painting speak on its own terms while contributing to a larger dialogue.

Technical contrasts are a major draw for anyone who loves the craft of painting. Rembrandt’s impasto and energetic scumbles sit next to pupils’ thinner glazes and smoother passages, and Vermeer’s meticulous surfaces stand apart. These differences reveal choices about subject, speed, and what each artist valued most.

The students’ paintings also show how market forces shaped careers in Rembrandt’s era. Some pupils adopted popular themes to sell portraits and genre scenes quickly, while others used the master’s name as a launchpad for riskier ideas. Economic reality often steered artistic evolution as much as taste did.

Visitors often find themselves reassessing what it means to be a “student” of a great artist. Apprenticeship did not always mean imitation; many pupils became innovators who redirected their teacher’s lessons in surprising ways. That complexity is part of the exhibition’s quiet argument.

Conservation work on these paintings brings another layer to the experience. Restorations and scientific imaging clarify authorship, reveal changes, and sometimes reassign works previously attributed to the master. Those discoveries feed into the ongoing story of how museums and scholars manage histories of influence.

The presence of a single, privately owned Vermeer also highlights how private collections interact with public exhibitions. Loans like this create rare moments of access, and the painting’s solitude in private hands lends it a little mythic aura in public view. Its inclusion is both a privilege and a lens for comparison.

Ultimately the show encourages close looking rather than quick judgment. It asks viewers to track technique, decision, and dialogue across a range of hands, from Rembrandt himself to the artists who learned from him and a lone Vermeer who stands apart. That kind of sustained attention rewards patience and curiosity.