Boston’s MFA Spotlights Winslow Homer and a Cross-Border Wilderness

While the loud disputes in the City of Brotherly Love grab headlines, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts quietly mounts a major exhibition devoted to Winslow Homer. The show gathers paintings and watercolors that trace his interest in rural life and rough seas, and it asks a simple question: why do these images still matter? That line of inquiry points to unexpected ties with landscapes north of the border.

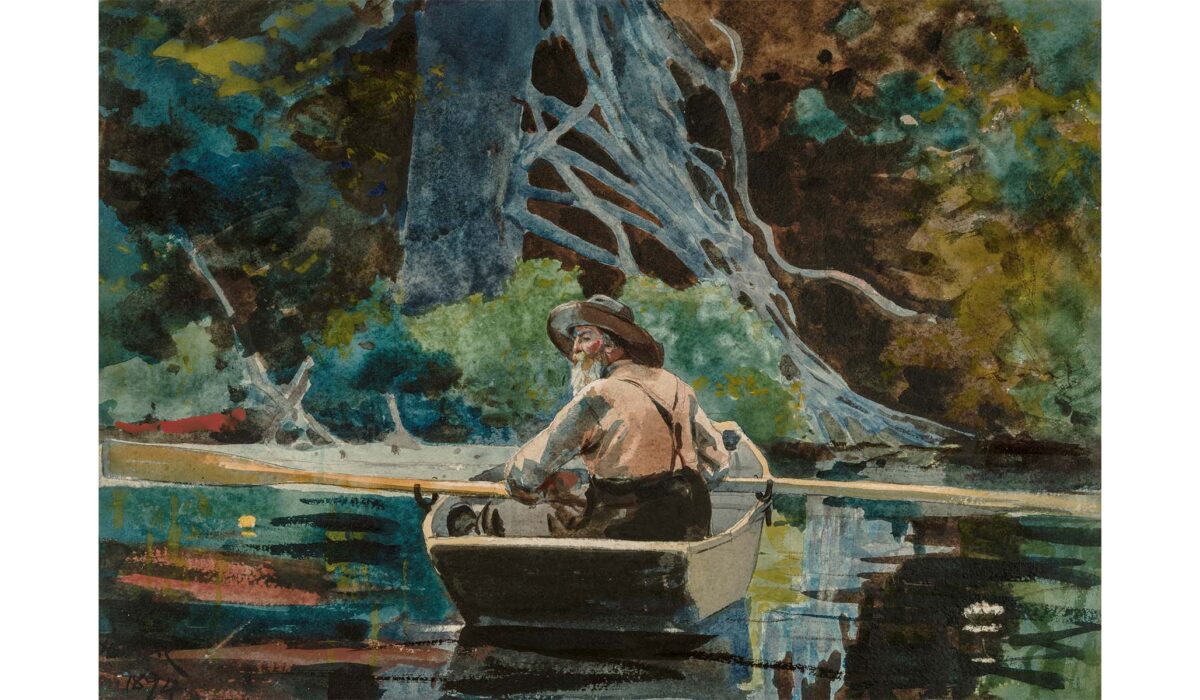

Winslow Homer is best known for powerful seascapes and crisp depictions of outdoor labor, and the MFA’s selection makes those strengths obvious. The canvases range from storm-battered coasts to hush-filled forest interiors, offering a compact school of his visual grammar. When you stand in front of the larger works you feel both the painter’s restraint and his appetite for place.

One recurring motif in this exhibition is the Adirondack guide, a figure who represents a certain frontier competence and quiet authority. Those guide portraits and camp scenes are rooted in a region that sits near Canada, so the imagery naturally echoes cross-border activities like trapping, logging, and guiding. The wilderness Homer depicts doesn’t stop at political lines; it’s part of a shared northern environment.

The show also highlights technique: Homer’s watercolors are exploratory and inventive, while his oils are often architectural in their solidity. The MFA arranges the pieces so you can compare a loose, brisk watercolor with a carefully modulated oil on the same subject. That side-by-side reading lets you see how Homer translated experience into different visual languages.

Cultural ties between New England and Canada are subtle here rather than shouted, expressed through common craftsmen, similar vernacular architecture, and a mutual reliance on seasonal work. Those details populate Homer’s scenes: a lean-to, a river crossing, the geometry of stacked wood. It’s easy to underestimate how much daily life shapes an artist’s subject choices, but this exhibition makes those invisible decisions visible.

The curators avoid flashy reinterpretation and instead give the works room to do their own talking, which is a useful restraint. Label text is concise and situates each piece in Homer’s chronology without forcing a single thesis. The result is a show that trusts viewers to make their own connections between picture and place.

For visitors who know the Adirondacks, the landscapes feel both familiar and sharpened by Homer’s eye; for those who do not, the paintings serve as clear introductions to a natural world organized by seasons and occupations. In either case the works reward slow looking, the sort of attention you would give to a conversation with someone who knows the woods. You leave with an awareness of technique and a sense of geography.

Photographic reproduction loses the textures that Homer layered into sky and water, which is another reason seeing the originals matters. There is a material presence to pigment on canvas that frames simply cannot reproduce, especially in the subtle reflections and the weathered hands he painted. The MFA makes that case quietly but convincingly.

Beyond aesthetics, the exhibition gestures at historical continuity: the same corridors of trade, travel, and seasonal labor that Homer painted still shape communities on both sides of the border. Museums are good at showing how objects hold time, and here the paintings act as timekeepers for a particular northern economy and set of skills. That connection is the exhibition’s most interesting thread.

If you want an encounter with Homer that emphasizes place over personality, this MFA presentation delivers. It leaves the noise of politics and spectacle outside and insists that art can be a map as well as a mirror. In doing so, it offers a tidy, thoughtful look at why those Adirondack scenes keep drawing our attention.