History gets messy when myth moves in and takes over the living room. I’ll look at who Columbus really was, separate invention from record, note the immigrant context, and explain why the flat Earth tale is wrong.

Let’s return to the genuine Columbus of the Italian immigrants and not to the fictional Columbus of the French revolutionaries and their flat Earth myth. That line guides this piece: it pushes us to consider Columbus as a person shaped by his era and loyalties, not as a cardboard villain or a cartoon hero.

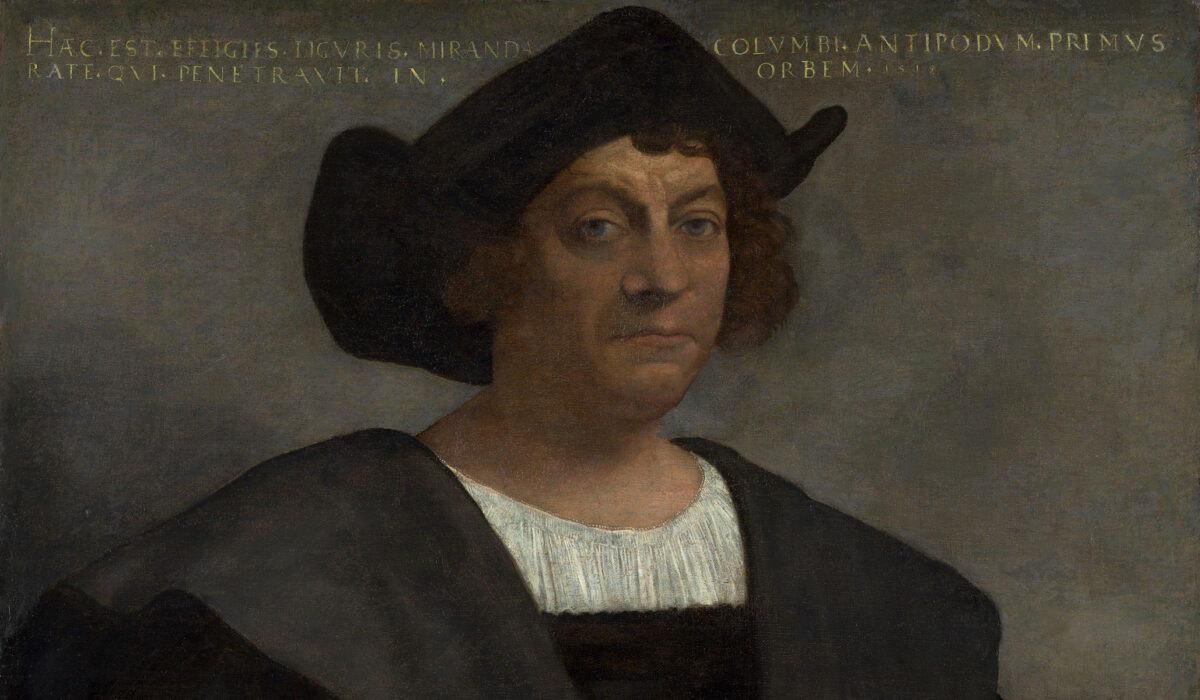

Christopher Columbus was a navigator working in a world of risk, commerce, and rival courts, and he sailed under Spanish crowns while keeping his Genoese roots. His voyages were commercial and political ventures as much as exploratory ones, motivated by trade routes, profit, and prestige. Treating him as a complex figure helps avoid simple, misleading narratives.

The flat Earth story is a powerful myth because it offers a simple contrast: enlightened explorers versus ignorant superstitions. In reality, educated Europeans of Columbus’s time understood the Earth was round. The myth largely grew later as a rhetorical tool in other cultural fights.

Immigrant communities have long used Columbus as a symbol for assimilation and achievement, especially Italian Americans who found a champion in a figure with Genoese origins. He became a cultural touchstone during waves of migration when people needed a story of arrival and endurance. That social role alters how Columbus is remembered and why debates around him feel personal.

At the same time, modern reassessments rightly examine the harms that followed European expansion, including violence and displacement. A clear-eyed history notes those consequences without collapsing into caricature. We can hold both the navigational feats and the human costs in view.

Books and documents from the era show a man operating inside the norms and brutal realities of early modern imperialism. Columbus wrote letters, kept logs, and negotiated with monarchs, and those records are the basis for any serious account. Using primary sources forces us to rely on evidence rather than later moralizing or romance.

Why do some versions of Columbus’s story insist on moral purity or total damnation? Simplified stories sell well because they answer big questions quickly. If we want honest history, we have to tolerate complexity and discomfort, which takes work and nuance.

Civic memory is fluid; statues, holidays, and school lessons reflect political choices more than settled historical truth. Communities decide which parts of the past to emphasize and which to quiet. Recognizing that helps explain why debates over Columbus flare up whenever society renegotiates its identity.

Teaching history should equip people to ask better questions: What did explorers actually do? Who benefited and who suffered? What motives drove actions, and what evidence supports the claims?

Those questions lead to a richer public conversation about heritage, responsibility, and how we honor the past. Changing how we talk about Columbus does not erase history; it shifts the focus from myth-making to critical understanding. That matters because the stories we pass on shape civic imagination.

We can preserve recognition of navigational skill and immigrant symbolism while refusing myths that distort the record. That balance respects both evidence and empathy, avoiding lazy heroism or reflex punishment. It’s not about defending a single figure; it’s about insisting on honest context.

That honest context returns us to the real, complicated man in his moment and the communities that later turned him into a larger symbol. It also invites clearer, calmer public discussion about memory and meaning. The point is to replace caricature with clarity.