Technocracy: How Experts Remade Modern Governance

The Cold War hardened a new assumption: scientific skill equals strategic power. The space race, nuclear arsenals, and advanced computing turned labs into frontlines and poured resources into research and education. The Soviet Sputnik launch in 1957 jolted the United States and accelerated federal investment, including the creation of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

That era elevated scientists and engineers beyond inventors to trusted policy advisers. The President’s Science Advisory Committee (1957) became a model for formal expert counsel across public health, environment, and economic planning. Systems analysis and game theory matured as ways to apply quantified thinking to strategy and policy.

Nuclear power shows how military-driven science migrated into civilian life, carrying both promise and peril. What began as weapons research soon produced reactors and electricity, and with that shift came new regulatory and ethical questions. The dual legacy of atomic technology kept technocratic debates front and center.

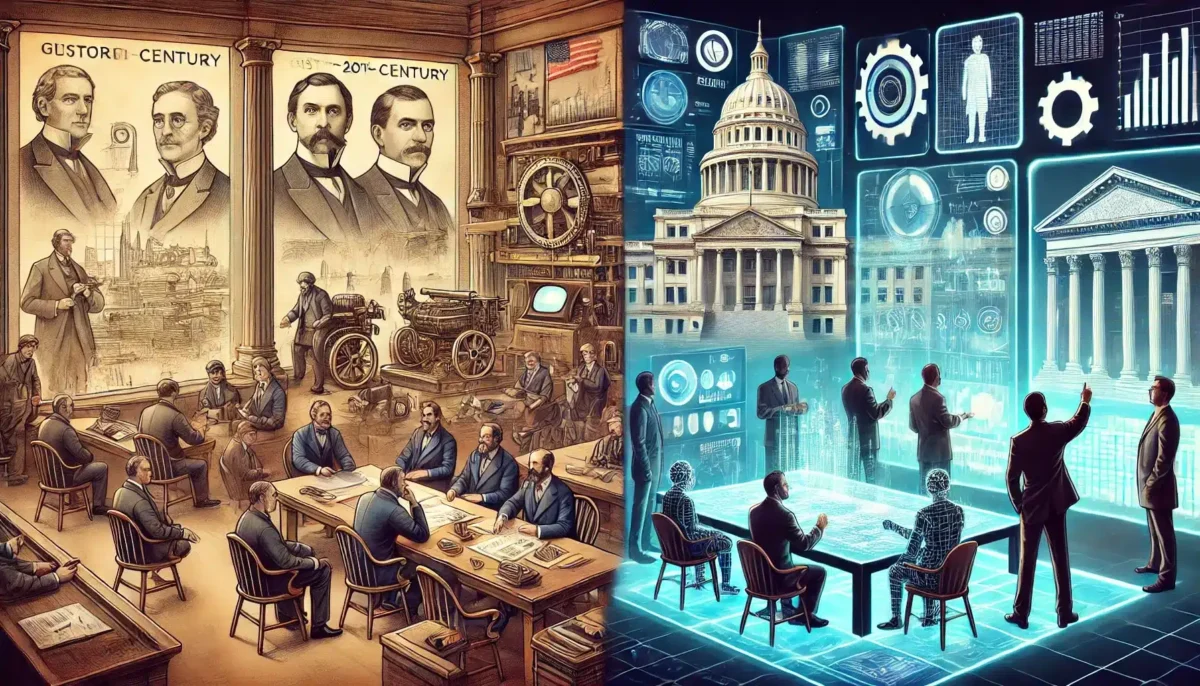

The American Technocratic Movement pushed the idea that technical expertise could replace or steady traditional political leadership. Thorstein Veblen’s critiques of waste and his focus on technological knowledge offered a philosophical backbone for that view. During the Great Depression, the Technocracy Movement formalized in 1932 and proposed engineers manage the economy by energy metrics rather than price signals.

Technocratic thinking influenced the Progressive movement and aspects of the New Deal without fully displacing elected officials. Large-scale public works and economic planning relied heavily on economists, engineers, and scientists who prioritized efficiency. Critics worried this practical expertise might marginalize social nuance and democratic accountability.

President Dwight Eisenhower warned Americans about the “military-industrial complex” in 1961, naming an uneasy alliance between the armed forces and defense contractors. That coalition functioned as a kind of technocracy where technical priorities could dominate policy decisions. The post-World War II boom in military R&D birthed missile tech, surveillance systems, and nuclear upgrades that validated his concern.

In a post-industrial society, the shift toward information and services concentrated power with those fluent in abstract, theoretical knowledge. Daniel Bell and others described how managerial and professional experts rose as a new class shaping policy and markets. Fields like computer technology, biotechnology, and environmental science became gateways to influence.

The rise of a professional managerial class brought data-driven decision-making into both corporations and government. Technocratic governance often favors empirical models, algorithms, and systems analysis, arguing complexity requires technical stewardship. The trade-off is a potential disconnect between technocrats and the broader public they serve.

Moreover, the concept of rationality itself is subject to debate. What counts as rational can vary across cultures and political goals, and scientific neutrality is not immune to social or economic framing. That insight undermines any simple claim that technical expertise equals objective governance.

Invisible expert influence can produce technocratic inertia: once a technical trajectory is chosen, institutional momentum resists alternatives. Research priorities, infrastructure plans, and procurement habits all reflect expert preferences and can crowd out competing values. That concentration raises persistent questions about transparency and democratic oversight.

Defenders of technocratic approaches argue against blanket technological pessimism and call for risk/benefit analysis instead of fear-driven rejection. They recommend safeguards and ethical frameworks so innovation aligns with social goods and human well-being. Historical evidence also shows technology improving living standards, reinforcing the case for cautious, evidence-based integration.

The conversation now is less about rejecting expertise than about balancing it with public judgment and moral concerns. Technocracy remains influential because technical know-how solves real problems, yet those solutions must be checked by democratic processes. The challenge is to harness expertise without surrendering accountability or human values.