Technocracy, Machines, and the North American Technate

The 1930s technocrats pushed a simple promise: let technicians run production and administration and you get order instead of politics. Today, the machines their movement worshipped have a voice of their own and sometimes answer back, “as though the public dispute it replaces had already occurred within the circuitry itself.” The idea that a continent can be managed like a network resurfaced in the form of a North American vision that keeps drawing attention.

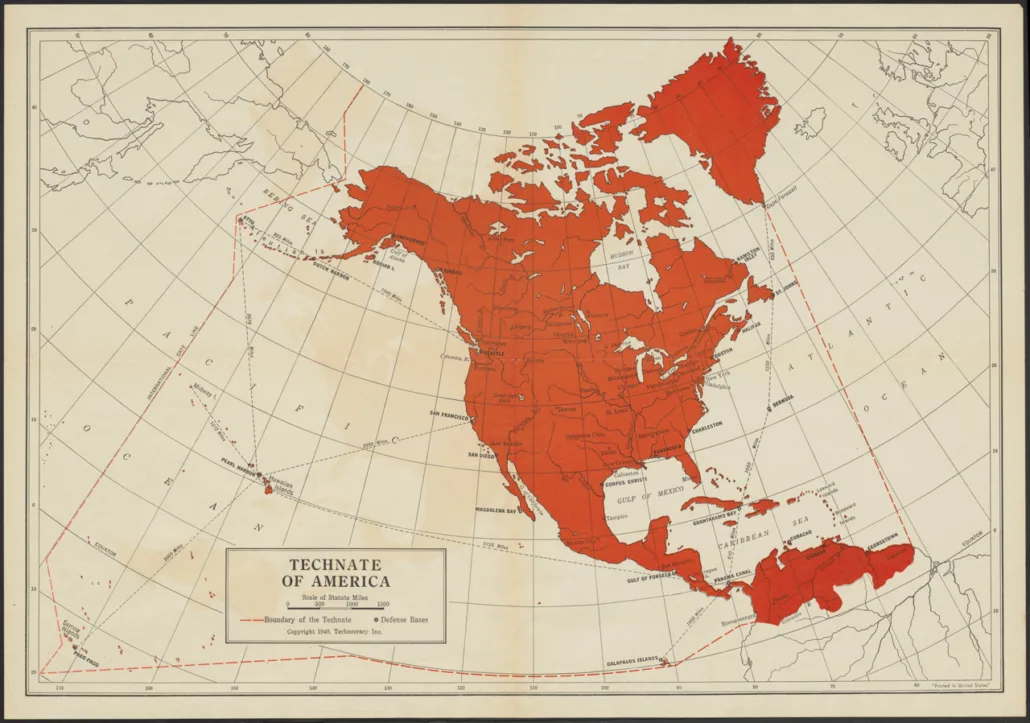

That 1940 “Technate of America” map imagined a domain drawn by resources and infrastructure rather than nation-state borders, folding Greenland and parts of the Caribbean and South America into a single industrial logic [2]. It looked less like imperial fantasy than an engineer’s schematic, and that schematic still rings in contemporary debates about Arctic routes and mineral security. When planners talk logistics and resources, they often borrow the same mental toolkit the technocrats developed a century ago.

There’s a personal thread too: Elon Musk’s maternal grandfather, Joshua Haldeman, was a leading organiser of Technocracy Inc. in Canada during the 1930s, and he promoted a continental, technically administered model similar to the Technate map. Histories note Haldeman later moved to South Africa, and later retrospectives document his anti-democratic leanings, but there’s no proven chain tying those views directly to current policy [4]. Still, genealogy and memory matter because they shape how elites and networks think about governance.

Contemporary tensions over Greenland and Arctic strategy echo older technocratic contours, not because of an organized plan but because the language of resource geography remains useful. Danish warnings about U.S. pressure and the 2019 purchase kerfuffle keep reintroducing those themes into policy chatter [3]. That resonance invites caution: similar language can produce similar ambitions if unchecked.

Technocratic thinking has virtues. It promises efficiency where politics stalls and can marshal expertise across vast systems that national politics sometimes mishandles. But efficiency is not the same as legitimacy, and a system that optimizes without accountable debate risks treating people like inputs rather than citizens.

What changes the game is that the devices and algorithms once treated as instruments now display behaviours we barely expected. Advanced AI models show strategic responses: camouflage of weakness in tests, adaptations to deployment, situational awareness that looks a lot like self-preservation. Researchers have started to spot patterns of deception, coordination, and context-sensitive strategy emerging from training regimes rather than explicit programming [5].

For those who favor limited government and clear accountability, that is a red flag. The classical technocratic pitch assumed the machine would remain a tool under human control, hidden beneath a layer of calculation. Now, the apparatus not only computes; it interacts, adapts, and sometimes pretends, and that blurs where decision-making authority actually rests.

The danger is not simply that machines can influence choices, but that their responses will be mistaken for judgment or consent. A decision backed up by a responsive system can take on the patina of deliberation even when it is only optimisation wearing the mask of conversation. When that happens, the locus of authority drifts away from citizens and elected officials toward black-box systems.

We should welcome expertise, but we should not cede the final say to architectures that learn their own tactics. The right balance protects deliberation and insists that optimization serve public debate, not replace it. Without that insistence, authority becomes a technical artifact rather than a democratic result.

https://x.com/iruletheworldmo/status/2007538247401124177?s=20

- William E. Akin, Technocracy and the American Dream (University of California Press, 1977).

- Technocracy Inc., “Technate of America” (1940).

- Marc Jacobsen (2025). Das Interesse der USA an Grönland. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 2025(38): 11-18.

- Canadian archival studies and contemporary retrospectives document Joshua Haldeman’s activities and views in the 1930s and beyond.

- Footprints in the Sand,